Solving Biology's Toughest Search Problem

The Needle in a Haystack: The Immense Challenge of Gene Discovery

In fields like therapeutics and agriculture, the promise of gene editing is immense. Yet, its success hinges on answering one critical question: which gene should we edit?

"In fact, target discovery is the biggest problem in therapeutics, even bigger than drug development itself." - Dr. George Yancopoulos, the Co-founder, President, and Chief Scientific Officer of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals.

The genome is a vast and complex search space. Identifying a single gene that can confer a desired trait is a monumental task. The traditional process involves years of painstaking literature review, hypothesis generation, and costly, time-consuming wet-lab experiments that often lead to dead ends. A researcher might spend 5-10 years validating tens of candidate genes only to find that one is viable. This bottleneck doesn't just slow down progress; it represents a massive expenditure of resources and delays the delivery of critical innovations to the field and the clinic.

The LLM and the Labyrinth: A New Approach to Biological Discovery

The core challenge in modern biology is not a lack of data, but our inability to reason across it at scale. Scientific knowledge is spread across millions of research papers and dozens of databases. To solve this, we need tools that can both understand the language of science and navigate the labyrinth of its interconnected facts.

While modern AI, particularly Large Language Models (LLMs), has shown incredible capabilities, standard approaches are insufficient for the complex reasoning required in biological discovery for these two reasons:

- The limits of RAG: Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) attempts to fix this by feeding LLMs relevant text snippets. However, it treats information as isolated chunks, fundamentally missing the interconnected nature of biology. RAG loses the "long-context reasoning" needed to connect a gene from a 2010 paper with a protein interaction from a 2018 study. It can find facts, but it can't reason across the entire network of knowledge.

- The Hallucination Problem: Standalone LLMs can invent information, a fatal flaw when accuracy is non-negotiable. They lack a deep, structured grounding in verified biological facts.

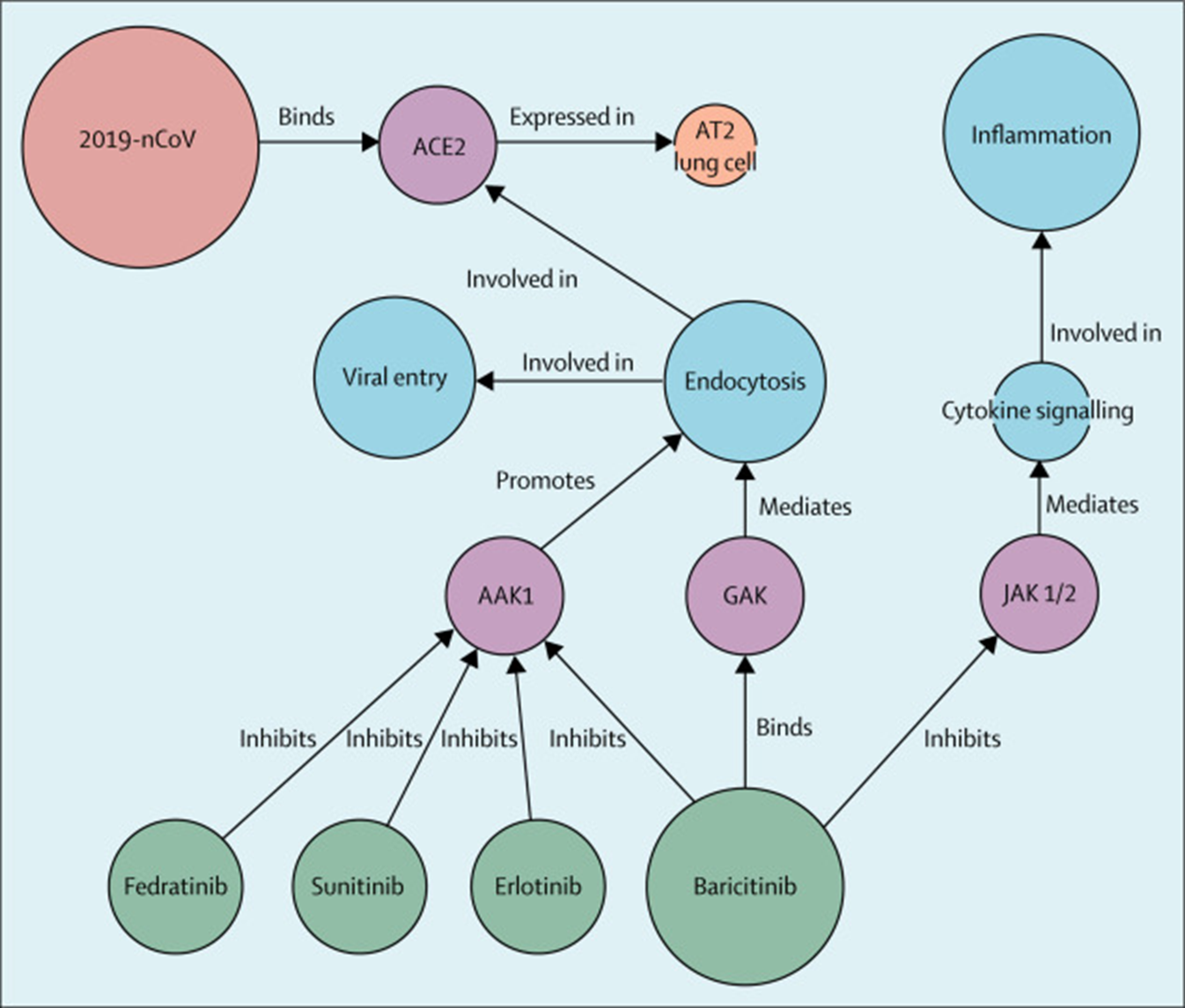

Knowledge Graphs (KGs) are the ideal solution for representing complex biological networks, mapping entities like genes and proteins and their intricate relationships. By creating a dynamic "brain" of biological knowledge, they allow an AI to uncover non-obvious patterns, as famously demonstrated when Benevolent AI used a KG to identify a potential drug for COVID-19.

However, KGs have their own significant limitation:

Traditionally, building, maintaining, and interpreting KGs is incredibly resource-intensive, requiring large teams with specialized knowledge in bioinformatics and data science. This has kept their power out of reach for most researchers.

The Synthesis: Combining LLMs and KGs for Breakthrough Results

Our solution overcomes these dual challenges by creating a powerful synergy where LLMs and KGs enhance each other.

- LLMs to Build the Graph: We use LLMs to do the heavy lifting of reading over thousands of scientific papers and automatically extracting factual relationships. This breaks the "Expert Bottleneck," allowing us to build a massive, literature-based KG quickly and efficiently.

- The Graph to Ground the LLM: We then use this highly structured KG to ground the LLM's reasoning. Instead of hallucinating, the LLM is forced to navigate the verified pathways within our KG. This provides the deep, long-context reasoning that RAG lacks, ensuring that the final output is both insightful and factually accurate.

By combining these approaches, we solved both problems. This synergy allowed us to build our massive, dual-KG system and make predictions with an accuracy that neither technology could achieve alone.

Case Study 1: Predicting a Salt-Tolerance Gene in Rice

This project collaborated with Balaji Santhakumar, a PhD scholar at Tamil Nadu Agricultural University (TNAU) specializing in agricultural gene editing.

The Research Problem: For five years, Balaji had been working to identify a gene that could confer the best salt tolerance in Indian rice varieties. Through extensive wet-lab experiments with six candidate genes, he had successfully identified one effective target. Crucially, at the time of this collaboration, his results had not yet been published.

The Challenge: Could our computational model predict his experimentally validated gene, a target that other state-of-the-art AI models had missed?

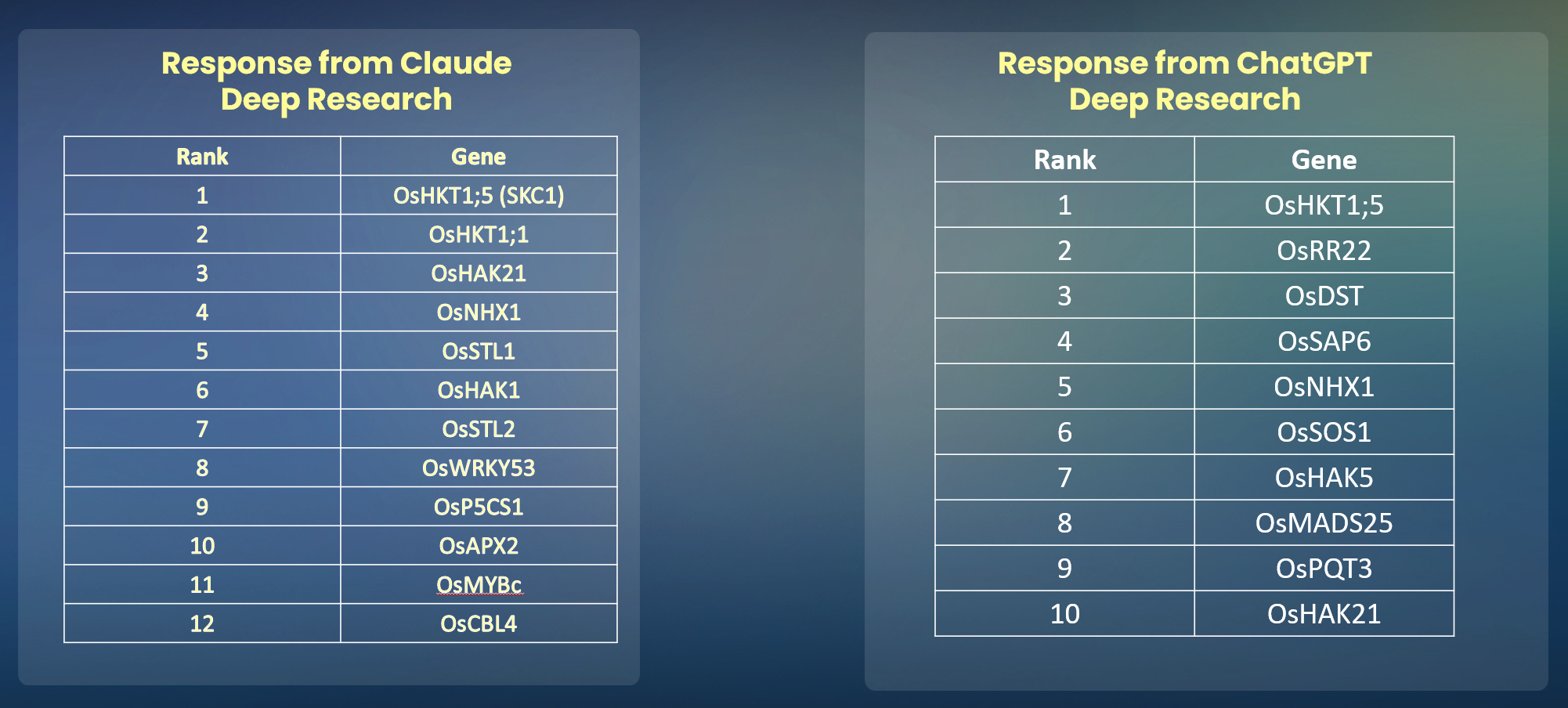

We tested our system against leading models like ChatGPT and Claude, which failed to place the correct gene even in their top 10 predictions.

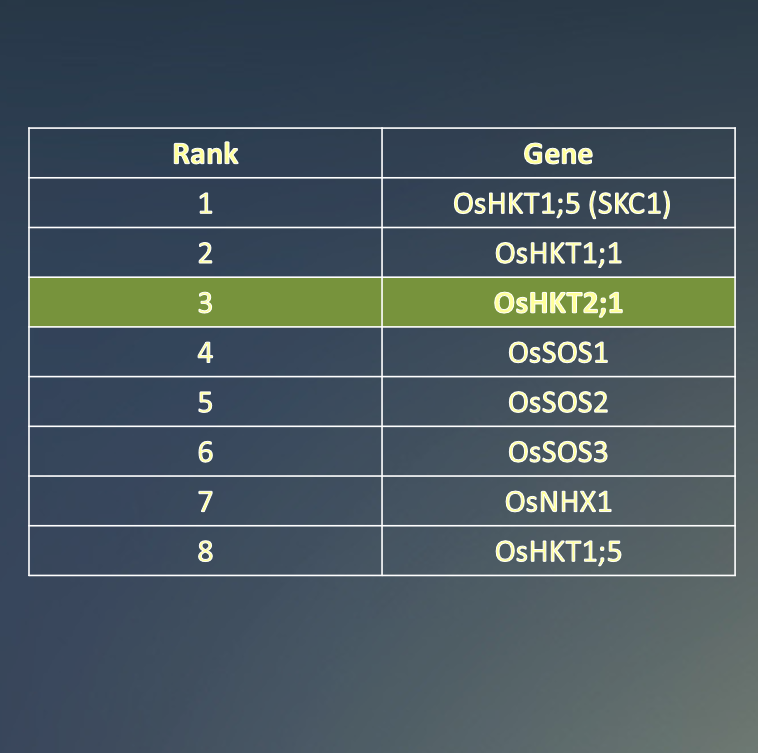

The Results:

Our Knowledge Graph-based model successfully predicted the correct gene,

OsHKT2;1, ranking it at number 3 in its list of candidates.

Validation:

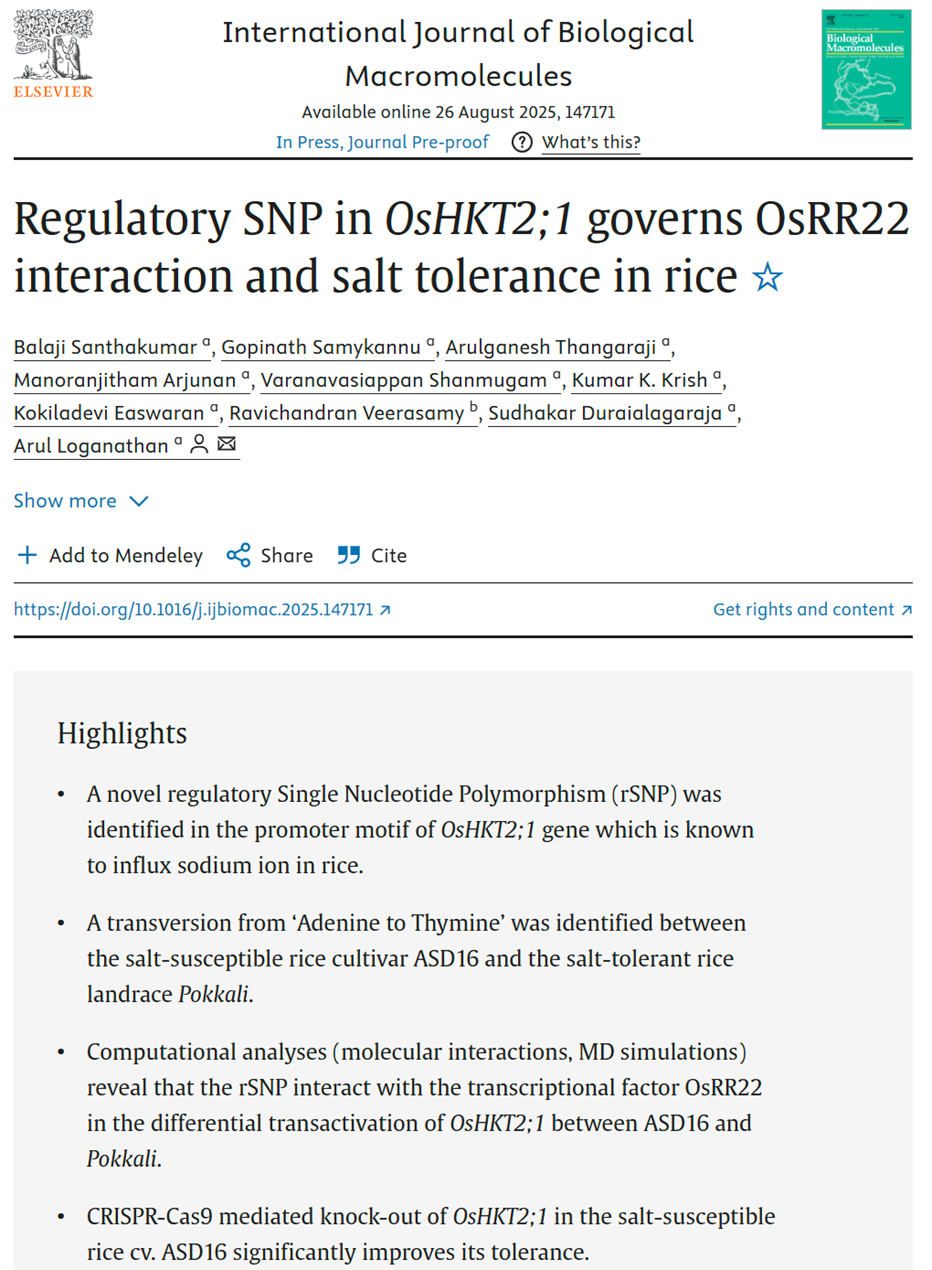

This prediction was later confirmed when Balaji Santhakumar published his findings. His paper, "Regulatory SNP in OsHKT2;1 governs OsRR22 interaction and salt tolerance in rice," validated thatOsHKT2;1 was indeed the gene he had identified through years of research. His work showed that a CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of this gene significantly improves salt tolerance in susceptible rice cultivars.

The Core Technology: A Dual Knowledge Graph System

To make such accurate predictions, we built two massive, interconnected Knowledge Graphs (KGs). KGs are powerful tools for integrating diverse data and uncovering novel biological relationships, a method famously used by Benevolent AI to identify a potential drug for COVID-19.

Our system is composed of:

- Unstructured Data KG: Built by analyzing the full text of over 1,500 research papers and scientific articles.

- Total Nodes: 35,472

- Total Relationships: 65,030

- Structured Data KG: Built from established biological databases like NCBI, UniProt, and Ensembl Plants.

- Total Nodes: 631,804

- Total Relationships: 5,862,138

- Cross-Database Mappings: 814,926

Methodology: How the KGs are Built and Queried

Building the Knowledge Graphs

- Unstructured KG (from Literature):

- Ingestion: We identify and process over 1,500 full-text research PDFs.

- Extraction: The text is chunked, and a Large Language Model (LLM) extracts biological relationships as triplets (e.g., Gene A - regulates - Gene B).

- Graph Construction: We use these triplets to build a graph, generate vector embeddings for each entity (node), and merge similar nodes to ensure consistency.

- Structured KG (from Databases):

- Data Sourcing: We ingest over 150 GB of data from public databases like NCBI Gene DB, UniProt KB, Reactome Pathways, and others.

- Harmonization: The data undergoes extensive cleaning, deduplication, and ontology mapping to standardize information across different sources.

- Assembly & Embedding: We use graph embedding models to merge similar nodes and relationships, assembling the final, validated KG.

The Prediction Pipeline

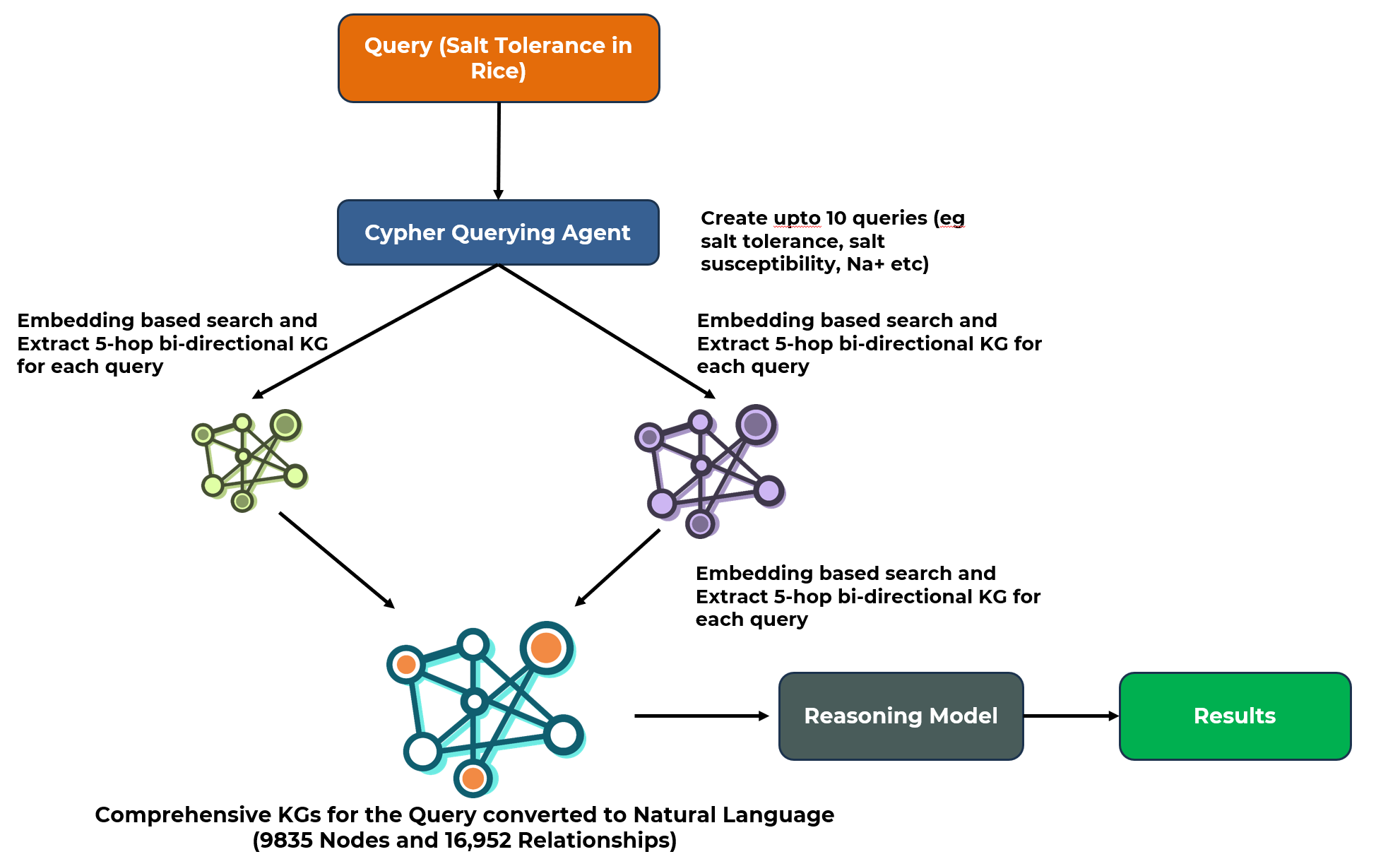

When a query like "Salt Tolerance in Rice" is initiated, the system executes the following steps:

- Query Expansion: A "Cypher Querying Agent" generates up to 10 related sub-queries (e.g., "salt susceptibility," "Na+ toxicity").

- KG Extraction: For each sub-query, an embedding-based search extracts relevant sub-graphs (5-hop bi-directional) from both the structured and unstructured KGs.

- Synthesis: These sub-graphs are merged into a single, comprehensive KG specific to the query.

- Natural Language Conversion: The synthesized KG is converted into natural language.

- Final Analysis: This text is processed by an advanced reasoning model to produce the final, ranked list of candidate genes.

Understanding how this works

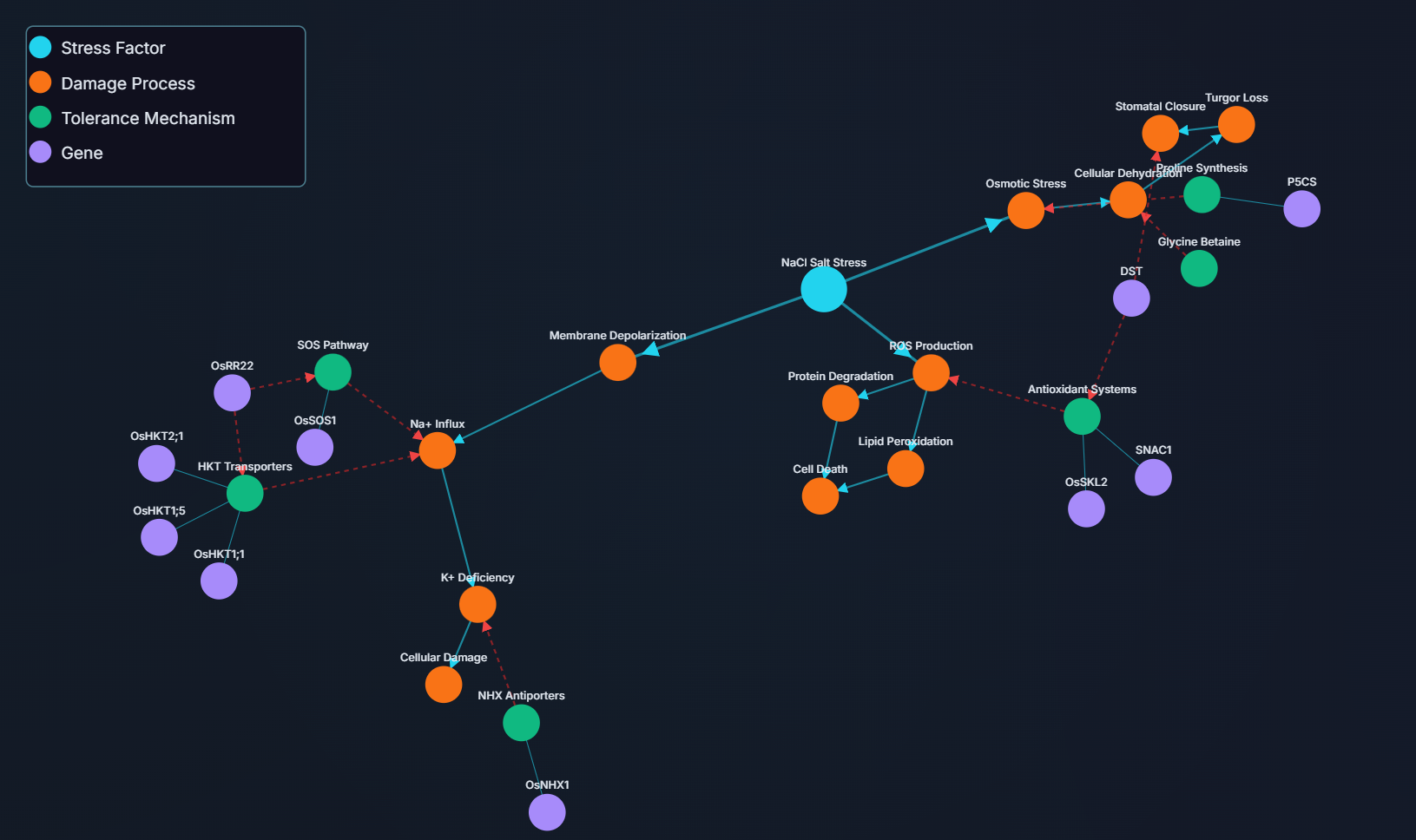

While the list above provides numerous targets, the true power of the Knowledge Graph lies in its ability to connect disparate pieces of information to uncover complex biological stories that simple analysis would miss. The gene OsHKT2;1 is a prime example of this long-context reasoning in action.

The Challenge: In scientific literature, the role of OsHKT2;1 can appear contradictory. It's known as a K+/Na+ selective transporter, but its direct impact on salt tolerance can be context-dependent, making it a difficult target to assess.

The KG's Synthesis: Instead of looking at the gene in isolation, the KG built a multi-step relational pathway by connecting several distinct nodes from across the dataset:

- Node 1 - The Gene: The graph identified OsHKT2;1 as a key ion transporter within the HKT family.

- Node 2 - The Regulator: It independently mapped the transcription factor OsRR22, identifying its function as a regulatory protein.

- Node 3 - The Interaction: The crucial step was connecting information from different sources that showed OsHKT2;1 interacts with OsRR22.

- Node 4 - The Functional Outcome: The graph also contained data showing that a loss of function in OsRR22 leads to increased salt tolerance.

The Insight: A simple analysis might just suggest overexpressing OsHKT2;1 because it's an ion transporter. However, by connecting these four nodes, the KG revealed a much more nuanced picture. It inferred that the regulatory pathway involving OsRR22 is a key control point. Since a loss of OsRR22 function is beneficial, and OsRR22 regulates OsHKT2;1, it strongly suggests that down-regulating or knocking out OsHKT2;1 could be a viable strategy to enhance salt tolerance.

Practical Implications for Target Discovery

The success of the salt tolerance case study demonstrates that this Knowledge Graph-based platform is a functional tool for accelerating target discovery. It directly addresses the primary challenge in biotech R&D: sifting through vast amounts of data to find viable targets for experimental validation. By providing data-backed hypotheses before lab work begins, this approach offers a more efficient path forward.

The core benefits of this technology are tangible:

- Accelerated Timelines: The platform can collapse research timelines from years to a matter of days. By rapidly identifying high-probability targets, it allows scientists to move directly to validation, saving significant time and resources.

- Reduced Research Risk: A major cost in biotechnology is experimental failure. This system provides strong, computationally-validated hypotheses that help researchers and companies focus their investments on the most promising candidates with greater confidence.

- Discovery of Novel Connections: The platform's key strength is its ability to find non-obvious connections across siloed data sources. As seen with the

OsHKT2;1andOsRR22interaction, it can propose novel gene functions and unexpected regulatory pathways that might be missed by standard literature reviews.

While this project was a proof-of-concept focused on agriculture, the methodology is applicable to any field reliant on genetic target discovery. A scaled-up version of this system could be a valuable tool for uncovering potential drug targets in human therapeutics by mapping complex disease pathways to identify new points for intervention. The technology represents a move toward a more rapid and data-driven process for the early stages of biological engineering.